In 2021, GBPI reflected on the unequal impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on economic security for Black women and Latinas. On May 11, the national public health emergency, which was declared more than three years ago, officially expires. During the pandemic, Georgians benefited from federal expansions to health care access via Medicaid, expansions to Unemployment Insurance (UI) and the Child Tax Credit, forbearances on federal student loan debts and other provisions that helped offset residents’ longstanding financial burdens exacerbated by the pandemic. Congress enacted several relief packages, including the American Rescue Plan Act, which sent Georgia $4.7 billion in flexible dollars. Georgia is holding approximately $6 billion in undesignated funding in state accounts and another $5.2 billion in its Revenue Shortfall Reserve, a “surplus” rooted in painful austerity politics. As the public health emergency ends, Georgians are forced to rely on a tattered state safety net while government leaders sit on a piggy bank of cash that could help fill holes temporarily plugged by federal supports.

Although the threat of COVID-19 is waning, disparate impacts for women of color persist. Black women and Latinas were hit hard by the pandemic and recession, faced disproportionate job losses and experienced the slowest recovery. It is up to states to enact legislation to strengthen economic security for households and prevent future disparate harms in advance of the next economic downturn. Georgia recently concluded its 2023 legislative session and did little to invest in equitable policies to support residents—particularly Black women and Latinas—through the COVID wind-down and beyond.

The Medicaid Unwinding Will Disproportionately Impact Black Women, Latinas and Their Children

One of the most significant pandemic provisions that has ended is access to Medicaid health coverage under the continuous enrollment provision that allowed millions of Medicaid-enrolled families to remain insured and access needed medical care throughout the COVID-19 national emergency. Almost 20 million people nationally enrolled in Medicaid during the public health emergency, including nearly one million[1] Georgians. The end of this continuous enrollment provision will result in losses of coverage for hundreds of thousands of Georgians with lower incomes. The burden of those coverage losses will fall heaviest on children and families of color. Black women and Latinas are most likely to lose eligibility if they are no longer pregnant and past one-year postpartum or if they are aging out of child eligibility. Those who lose eligibility might qualify for the Georgia Pathways to Coverage Program or marketplace coverage, or they might fall into the coverage gap.

About half of all Black and Latinx children—53% of all Black children and 49% of all Latinx children compared to about 23% of all white children[2]—are covered by Medicaid or PeachCare. Many children will lose coverage even though they are still eligible and get caught up in the churn as enrollees are reprocessed, which will impact economic security for their families. For example, a parent takes their child to the emergency room for an asthma attack or a broken arm and doesn’t realize they have lost coverage resulting in a devastating medical bill.

Georgia lawmakers chose to partially expand Medicaid eligibility through the state’s Pathways to Coverage Program that will launch July 2023, but it imposes burdensome work requirements and administrative barriers for enrollees and staff and will cost the state more and cover fewer Georgians than fully closing the coverage gap.

Employment Trends Signal a Return to the Status Quo

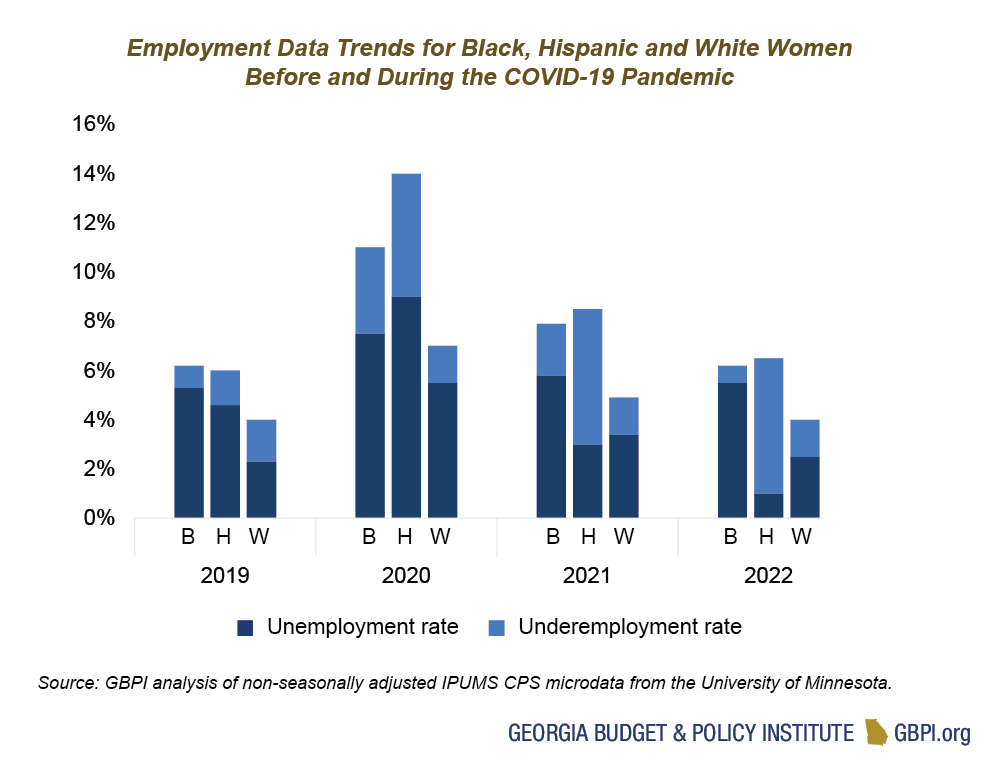

Unemployment and underemployment data trends from 2019 to 2022 for Black, Hispanic and white women signal a return to the status quo (see chart below). Although employment data for 2022 reflects pre-pandemic levels, Black and Hispanic women still suffer most. Additionally, even though unemployment for Hispanic women improved significantly in 2022, job quality remains low, as evidenced by the high underemployment rate that is slightly above pre-pandemic levels. The underemployment rate for Black women and Latinas in 2022 was 6.2 percent and 6.5 percent respectively, compared to 4 percent for white women.[3] Higher rates of underemployment indicate that many Black women and Latinas are working in jobs with reduced or part-time pay, and others want to work but have not found jobs due to various economic reasons including racial and gender discrimination in employment practices.

Black women and Latinas typically experience low UI enrollment levels due in part to being paid lower wages or having jobs that don’t meet UI eligibility thresholds. Instead of reforming UI and expanding access for workers, Georgia lawmakers passed SB160, which reduces the UI contribution by business owners and impedes replenishment of the UI trust, perpetuating Georgia’s reliance on harsh UI eligibility standards that could continue to leave Black women and Latinas without UI protections if they lose their job at no fault of their own. This could have huge consequences during the next economic downturn, which some economists forecast we are heading in that direction. During the next recession, federal lawmakers may be more reluctant to provide supplemental UI protections to address inadequate state UI programs leaving Georgia workers—particularly Black and Latinx workers—more vulnerable to hardship.

Pay Inequality for Women of Color Persists

The gender pay gap, the difference in pay between men and women, is another factor impacting Black and Latina women’s economic security and recovery. In Georgia, there is a $10,000 wage gap in median earnings between male and female workers. Although Black women have the highest labor force participation followed closely by Latina women, they earn just 64 cents and 54 cents respectively for every dollar earned by their white male counterparts. This is due in part to racial and gender discrimination in hiring and occupational segregation. It is also related to the value we place on certain industries and occupations in this country. Research shows that work valued as men’s work is paid a higher premium than work seen as women’s work. For example, according to Department of Labor statistics, more than 97% of preschool and kindergarten teachers are women who are paid a median annual salary of $34,426. Comparatively, roughly 96% of maintenance and repair workers are men who are paid a median annual salary of $50,900. Across all occupations, women are paid less than men for doing the same work. Even in women-dominated occupations—child care workers, dental assistants, secretaries and administrative assistants—women make less than men (e.g., the median annual salary of women dental assistants is $35,092 compared to $40,485 for men). And the gap is even wider for women of color.

Indicators of this gender-based valuing of work can be found in the Georgia state budget. Most Georgia state workers are women. Black workers are the largest group of state workers, and women nearly double men in the state workforce. The base salary for an entry-level eligibility worker, an Economic Support Specialist 1, at the Department of Family and Children’s Services (DCFS) is $32,000. Although approximately $11 million was added to the budget for DCFS to hire up to 450 eligibility caseworkers and promote 75 supervisors to prepare for the Medicaid unwinding, no funds were allocated to boost workers’ pay above the $2,000 cost-of-living adjustment. Teaching is another female-dominated industry. Roughly 80 percent of teachers in Georgia’s PK-12 grade schools are women. The FY2024 budget includes a $2,000 raise for educators, but the starting salary is just over $38,600 in Georgia. Additionally, lawmakers appropriated $13.1 billion, the most ever, to fully fund Georgia’s Quality Basic Education (QBE) K-12 funding formula for AFY 2023 and FY 2024, but the formula is antiquated and provides no funding specifically to educate students living in poverty.

Georgia’s Safety Net Needs Further Repair

While there were some victories this Legislative Session that will benefit Black women and Latinas, other harmful policies continue to threaten their economic security and well-being. Currently, about 18 percent of Black women and 19 percent of Latinas live in poverty in Georgia compared to 10 percent of white women.[4] Georgia’s Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) or cash assistance program is woefully insufficient to meet families’ needs. The program reaches only five families for every 100 families in poverty. The low benefit amount of $280 per month for a family of three hasn’t increased in over 30 years, a paltry sum that fails to account for inflation and rising costs of housing and groceries. However, one triumph this session was the passage of HB129, which expands access to TANF for pregnant women and eliminates the outdated TANF family cap. The family cap denied access to benefits for children born while any family member was receiving cash aid, another TANF program feature rooted in racist beliefs that Black women were having additional babies to receive more benefits. Studies found that there was no relationship between family caps and a reduction in births. The elimination of the family cap is a small improvement to cash support for birthing people and their children. However, it doesn’t address the full financial need, which has potentially grown since Georgia’s six-week abortion ban (HB 481) was implemented.

Need-Based Aid for Higher Education would Better Support Students

The FY2024 budget funds the HOPE Scholarship at 100 percent of tuition. However, Black students are among the least likely to receive HOPE or Zell Miller scholarships, and are underrepresented among recipients of the Zell Miller scholarship compared to their representation among students. A more equitable solution that would benefit students of color, particularly Black women who carry the most student loan debt of any group due to the intersecting gender/racial wage and wealth gaps, would be to fund need-based scholarships.

Governor Kemp vetoed HB 249, which passed with overwhelming bipartisan support and would have lowered the percent of the credit requirements toward the credential to qualify for a “college completion grant.” HB 249 would have decreased the initial eligibility from 80 percent to 70 percent for students in a four-year program and from 80 percent to 45 percent for students enrolled in two-year programs. It also would have raised the maximum award per eligible student from $2,500 to $3,500. HB 249 was a step in the right direction towards funding need-based aid. Black students are more likely to drop out of college due to financial challenges, and nearly two-thirds of Black and Latinx student borrowers attending for-profit, four-year schools drop out, and with more debt than their white peers. The expansion of completion grants can help students get to the finish line.

However, a more comprehensive need-based aid program would provide students entering college with aid based on their financial needs. Like the federal Pell Grant, students would receive funding on a sliding scale instead of a “one size fits all” approach. To achieve this, need-based aid would ideally be administered by the individual institution rather than a central hub like the Georgia Student Finance commission, which administers the HOPE scholarship. More must be done to support students and end the cycle of student debt that hampers their economic mobility.

Conclusion

It is a long road to economic security for Black women and Latinas in Georgia, but it is possible. Raising the state minimum wage and ensuring equal pay, strengthening the safety net by funding the UI trust and raising the TANF benefit amount, enacting a refundable state earned income tax credit, providing paid family and medical leave for all workers and funding need-based aid are just a few opportunities for lawmakers to improve Georgians’ overall economic well-being and strengthen their resiliency to withstand the next downturn. When Black women and Latinas are better supported by policies, we all will benefit.

End Notes

[1] GBPI analysis of (1) CMS enrollment data and (2) DHS’ 2023 Medicaid enrollment estimate: (1) data.medicaid.gov. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2023). State Medicaid and CHIP applications, eligibility determinations, and enrollments data [data set]. Retrieved April 20, 2023, from https://data.medicaid.gov/dataset/6165f45b-ca93-5bb5-9d06-db29c692a360/data; (2) Georgia Department of Human Services. Medicaid unwinding. Retrieved May 8, 2023, from https://dhs.georgia.gov/medicaid-unwinding.

[2] SHADAC analysis of Health Coverage Type by Race/Ethnicity and Age, State Health Compare, SHADAC, University of Minnesota, statehealthcompare.shadac.org, Accessed May 1, 2023.

[3] GBPI analysis of non-seasonally adjusted, IPUMS CPS microdata from the University of Minnesota.

[4] GBPI analysis of U.S. Census Bureau’s America Community Survey 2021 5-year data.